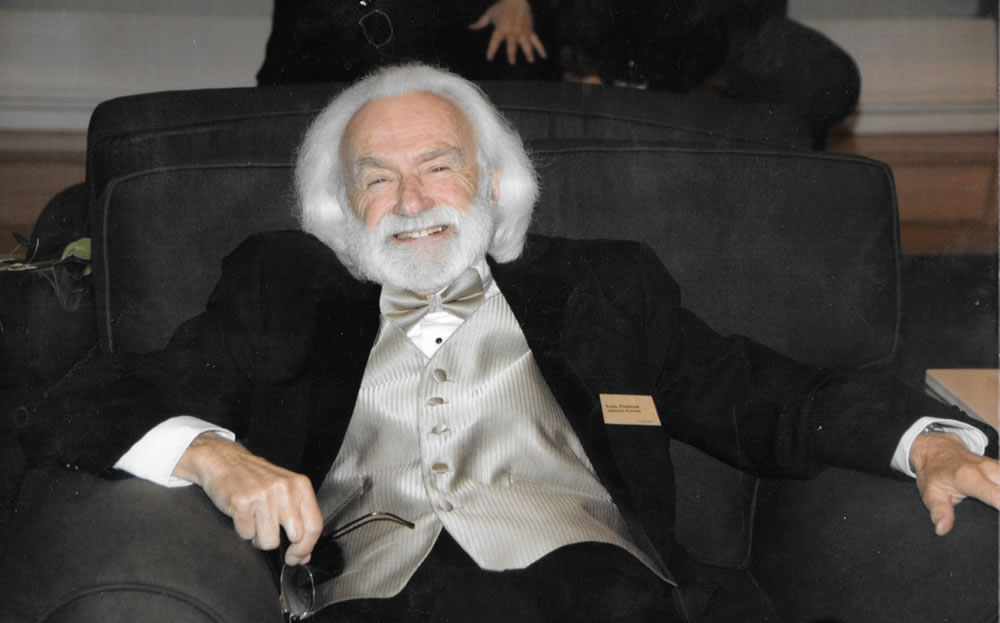

Karl H. Pribram

Karl H. Pribram, the eminent brain scientist, psychologist and philosopher, died in 2015, at the age of 95, at his home in Virginia.

Dr. Pribram has been called the “Magellan of the Mind” for his pioneering research into the functions of the brain’s limbic system, frontal lobes, temporal lobes, and their roles in decision making and emotion.

Karl H. Pribram is author of more than 700 publications, including data and theory papers, as well as books, such as Plans and the Structure of Behavior (1960) with George Miller and Eugene Galanter; Languages of the Brain (1971); Brain and Perception (1991); Freud’s Project Reassessed (1976) with Merton Gill, and The Form Within: My Point of View (2013).

Featured Quotes

What makes humanity humane

Karl H Pribram

Introduction

Reviewing what I wrote more than three decades ago [1] makes me exclaim: It’s pretty damn good. Who wrote this? I’m sure many of you have had this feeling about some- thing that you composed some time ago.

Almost everything I wrote back in 1970 I’ll vouch for today – and in some cases the earlier statements express my ideas better than I am doing currently. A case in point, one that I am going to pursue in this essay, concerns the topic “coding”. I had forgotten that, what today I have been subsuming under the rubrics “complexity”, “non-linear dynamics” and “chaos theory” is in fact what codes are all about.

Reference

1. Pribram KH: What Makes Man Human. James Arthur lecture on the evolution of the human brain. New York, The American Museum of Natural History; 1970 Published in J Biomed Discovery Collab 2006, 1:.

The History of Neuroscience in Autobiography

Karl H Pribram

My interactions with B.F. Skinner at Harvard were especially memorable and led to a decade of primate operant conditioning experiments, which developed into subsequent research in cognitive neuropsychology. Shortly, I was able to automate and extend the operant equipment to record (including reaction time) the results of individual choices among a dozen possible panel presses. Later, over my three decades at Stanford (1959-1989), these responses were recorded in a large variety of problem-solving situations. The computer-controlled testing apparatus was dubbed Discrimination Apparatus for Discrete Trial Analysis (DADTA).

At one point in our interaction, Skinner and I came to an impasse over the possible mechanism involved in the chaining of responses. Chaining was disrupted by resections ofthe far frontal cortex. Skinner suggested that proprioceptive feedback might have been disrupted, but this hypothesis was not supported by my experiments. Furthermore, as I indicated to Skinner, he, as a Ph.D. in biology, could propose such an hypothesis, but I, as a loyal Skinnerian, had to search elsewhere than within the “black box” for an answer to our question. George Miller overheard some of our discussions and pointed out to me that he had available a procedure that made chaining of responses easy: a computer program. Miller explained to me the principles of list programming which he had just learned from Herbert Simon and Alan Newell. The culmination of the collaboration begun by these encounters in the halls of Harvard was Plans and the Structure of Behavior, a book influenced also by our interactions with Jerome Bruner, who had organized a conference on thinking at Cambridge University in 1956 to which we had been invited. The book was written in 1958-1959 at the Center for Advanced Studies in the Behavioral Sciences, adjacent to the campus of Stanford University.

Recent updates from the Karl Pribram Archive and related works.